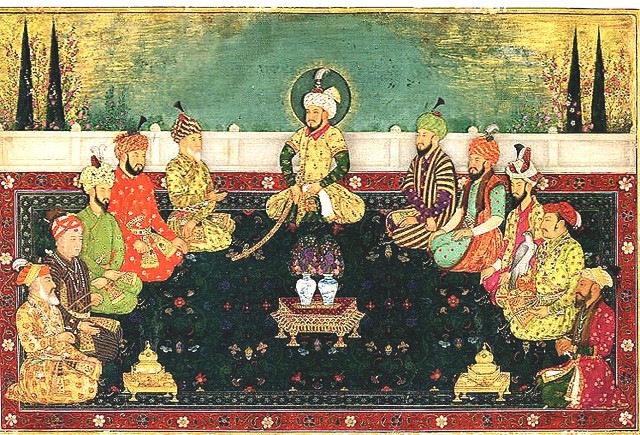

Mughal empire is a significant episode of Indian history, marking the zenith of pre-democracy India. Like every other empire, it had its bright and dark sides. History is about objectively examining both facets of your subject. Similarly, not all Mughals were the same, only a few of them were truly exceptional for their gifts, execution, achievements, and legacy. Here, I will talk about the three Mughal figures I find truly exceptional.

Princess Jahanara (1614 – 1681)

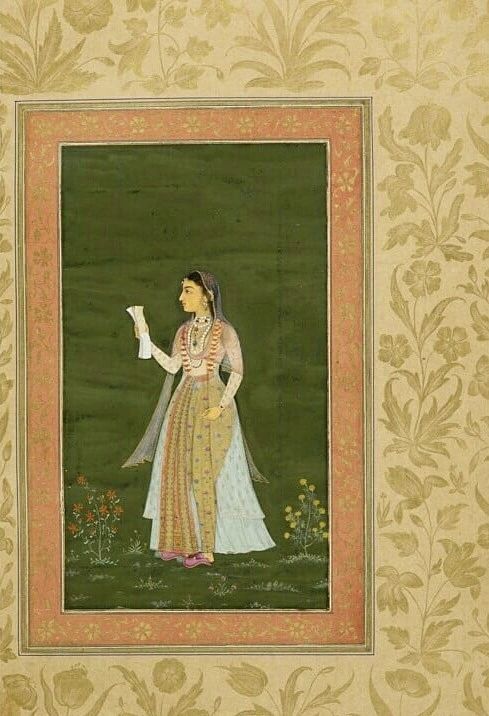

I find Princess Jahanara the most exceptional of many remarkable Mughal women. Jahanara was the eldest daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan and Empress Mumtaz Mahal and was a very bright girl. Following the demise of Mumtaz Mahal in 1631, Shah Jahan chose Jahanara over any of his wives to become the First Lady of the Empire (Padshah Begum). As the First Lady, Jahanara took over an establishment of several thousand women in a number of departments headed by women. Jahanara immediately took to her new role and was liked and respected by all.

Jahanara was a beautiful lady, inheriting her mother’s looks. Taking on her mantle, Jahanara looked after her younger siblings and arranged their marriages. She was also an avid reader and a keen learner. She was well versed in Persian, Turkish, and Arabian literature and in religion and philosophy. She built some exquisite gardens like Bagh-e-Jahanara, Bagh-e-Nur, and Bagh-e-Safa. She was so adored by her father that Jahanara was the only Mughal woman who was weighed against gold and precious stones on her birthday, like the emperor.

Jahanara had a keen eye for business and actively participated in the empire’s trade ventures. She made Chandni Chowk and some of the other buildings in Delhi. She also made an elegant serai (a lodging place for travelers) at one end of Chandni Chowk. Francois Bernier, who visited the Mughal court, writes fondly of the serai, wishing Paris had an equivalent to boast. Jami Masjid of Delhi was also sponsored and funded solely by her.

Young Jahanara was very ambitious for carving a distinct place for herself and leaving her mark in the intensely patriarchal world she was a part of. She built a marvelous garden called Sahibabad, which was the biggest green area in Old Delhi. It was a walled garden spread over an area of 50 acres with summer pavilions set within ponds, hidden behind fountains.

Niccolao Manucci describes Jahanara as the richest woman in the world at that time, receiving revenues from a number of territories within the Mughal Empire as well controlling the prosperous port city of Surat. She enjoyed the exceptional privilege of having her own palace outside the walls of the Agra Fort.

Jahanara was very fond of her father and served as his chief advisor and confidante in administrative matters. She was also the first ever Mughal woman who was given the imperial seal for affixing to the imperial edicts. After a decade of playing a stellar role as Padshah Begum, and at the age of twenty-seven, Jahanara expressed her desire to step away from materialistic desires and start her journey as a Sufi abstainer.

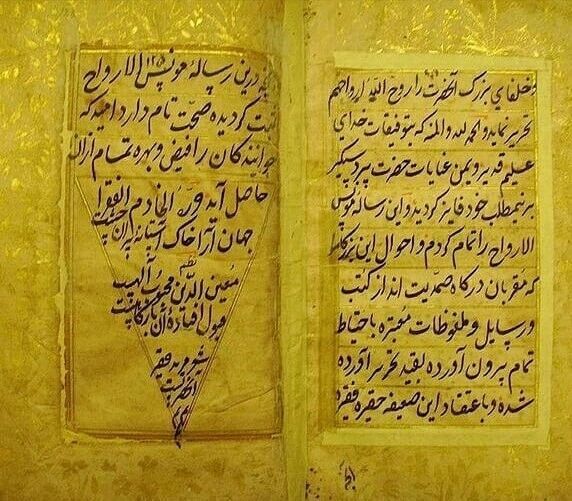

She had a special bond with her brother Dara Shikoh, forged by the similarities in their philosophical, intellectual, and artistic interests. They both pursued Sufism and wrote their first books on Sufism at the same time. Dara authored “Safinat-ul-Auliya” (The Ship of Saints) that details some of the major Sufi orders. Jahanara wrote “Munis-al-Arwah” (Confidant of Souls) that is a detailed biography of Muin-ud-Din Chishti plus an account of five other saints of Chishti order. Jahanara also wrote Risala-e-Sahibiya (Epistle of Companionship), sharing her spiritual journey and beliefs with us along with the life sketch of her murshid (spiritual guide) Mulla Shah Badakhshi. This is an extraordinary piece of work, preserved as the only autobiography from a Mughal empress. Apart from being an erudite person, Jahanara also patronized poets and scholars. Mir Mohammad Ali wrote a famous masnavi praising Princess Jahanara’s generous sponsorship of artists and scholars.

Soon a brutal war of succession broke out among Shah Jahan’s sons and Jahanara sided with Dara. However, it did not break her affectionate bond with her other three brothers. The letters exchanged between the princess and her brother Aurangzeb around that period of time are ample testimony to it. Aurangzeb still trusted his sister and often wrote to her to intercede with their father on his behalf. She did redeem Aurangzeb in the eyes of their father after he had fallen in disfavor of the emperor on a couple of occasions. Jahanara also gave Aurangzeb valuable advice, like the auspicious astrological time to enter a city he was going to conquer. There was a frequent exchange of presents between the two. She even proposed the division of the empire among her brothers. However, men’s ambitions and egos were too rapacious to heed such counsel.

When Aurangzeb won the succession war, he made Roshanara -Jahanara’s younger sister who had supported Aurangzeb’s claim to the throne- the Padshah Begum as Jahanara preferred accompanying her ageing father who had been under house arrest by Aurangzeb. She became the former emperor’s solitary attendant until he died eight years later. During all those years, Jahanara never wavered from resting by the side of her father.

It is fascinating that in the midst of blatant selfishness all round her how Princess Jahanara -the most powerful woman of Mughal history whose favor everyone strove to seek, who conceived and built sumptuous gardens, bazaars, and buildings, who owned trade ships, and who possessed the imperial seal- so nonchalantly forsook her imperial life to move into imprisonment with her devastated father. During her years in house arrest, Jahanara also looked after and brought up her niece Jahanzeb Begum, the daughter of her beloved brother Dara Shikoh, who was left as an orphan after the war of succession. During those eight years there is not a single instance on record when Jahanara appealed or complained to Aurangzeb for anything.

After Shah Jahan passed away on January 22, 1666, Jahanara returned to court life. Such was the respect Jahanara commanded for her character, ability, and wisdom that despite her having been a partisan of Aurangzeb’s opponent in the war of succession, Aurangzeb immediately made her the Padshah Begum, replacing her sister Roshanara. As Padshah Begum, Jahanara would again wield considerable influence and command widespread respect. She would not hesitate to express her dissent when she did not agree with Aurangzeb’s decisions or views. For instance, she openly opposed Aurangzeb’s decision in 1679 to reimpose Jizya tax on non-Muslims, which had been abolished by Akbar 115 years ago.

Jahanara had witnessed men’s wars for thrones in her family all her life. As a child she saw her father fighting against his brothers for the throne. Throughout her best years she saw the same internecine fight among her own brothers. Then in her late life she saw her nephews rebelling against their father Aurangzeb. This princess passed her life always maintaining her dignity and fairness amidst the fray and always trying to mend what the lust of the throne would break.

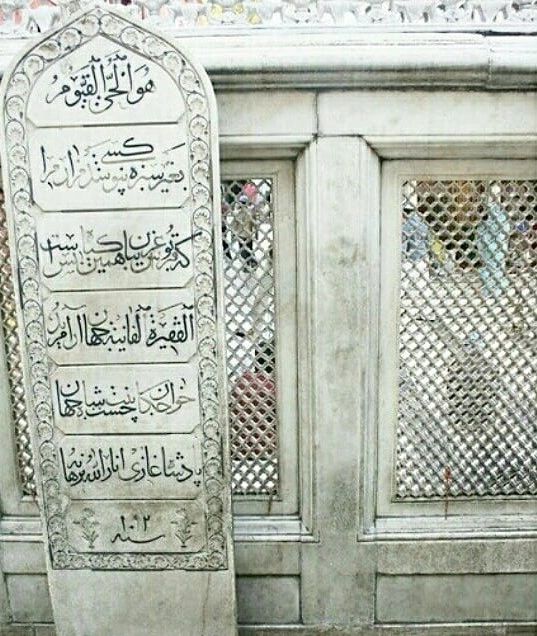

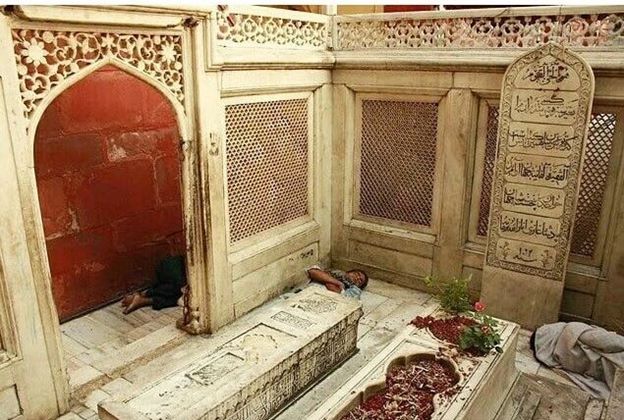

Princess Jahanara passed away in 1681 in Delhi. During her life, she had already commissioned a simple tomb for herself, entirely made of white marble, and located in Nizamuddin Auliya’s dargah in Delhi as her final resting place. Princess Jahanara’s epitaph begins with God’s name:

‘Hayyul Al Qayyum’ (He is the Living, the Sustaining)

The next two lines are a verse written by her:

“Baghair subza na poshad kase mazar mara

Ki qabr posh ghariban hamin gayah bas-ast”“There cannot be any other curtain of my tomb except the humble covering of grass.

Grass alone is sufficient to cover the grave of a fakir, a poor person, as I am”

The remaining lines in the plaque read:

The mortal simplistic Princess Jahanara, Disciple of the Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chishti,

Daughter of Shah Jahan, the Conqueror

May God illuminate his proof.

1092 [1681 AD]”

Amidst the daily hustle-bustle of Nizamuddin, the woman who was the most powerful during her time, continues to sleep peacefully in her tiny marble enclosure that she chose for herself. Her Sufi mysticism had taught her humility, the importance of helping others, and the beauty that lies in compassion.

While others showered her with titles, Jahanara chose to call herself a fakeera. With the staggering fortune she possessed, she could have built herself a mausoleum of any grandeur. But this daughter of Shah Jahan had a different perspective about what makes a person finally rest in peace. She wanted her tomb to be surrounded by nothing but grass. Nothing to plunder and when someone tramples upon the grass, it will regrow.

She was posthumously bestowed the title of “Sahibat-uz-Zaman” (Mistress of Time) by Emperor Aurangzeb who was deeply disturbed by her death. However, the reward after her death that would probably most make her happy is that she lies buried between the tombs of Nizamuddin Auliya and his greatest disciple, Amir Khusrau in an unpretentious carved marble enclosure beneath the open sky, covered with grass. It is probably poetic justice that in death this remarkable woman found her rightful place to sleep. The green vines still grow on her grave, as she wanted. Sleep on, Jahanara!

Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (1542-1605)

Akbar was the mightiest and most remarkable of Mughal kings. He had to rebuild and expand his grandfather Babur’s empire all over again. While his father and Babur’s son Humayun had inherited Babur’s love for literature, it was Akbar who was the true heir of his grandfather’s ambition, leadership qualities, and military genius. Humayun was too gentle and trusting for a king. Undermined by his conspiring brothers, Humayun lost his kingdom to Sher Shah, the ruler of Bengal and a ruthless tactician and an ambitious conqueror.

The Mughal family and their cohorts left Hindustan, back to their nomadic days while hitting the road again as fleeing refugees. As Humayun was on the run as a fugitive, he married a girl named Hamida. During this period Hamida gave birth to a son in the Rajput fortress of Umerkot, where Humayun had found refuge with its ruler, Rana Veersal. Humayun named his son Jala-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar. Born under such dire circumstances, this child would go on to shape the glory of the Mughal Empire and Hindustan. Akbar had a turbulent childhood right from his birth as his father was on the run and he too often parted or was taken away from his parents for extended periods.

Meanwhile Humayun reached the Safavid Empire with only forty of his companions surviving the ordeals and without Akbar who was in Kandahar after being kidnapped by Humayun’s brother, Askari. Shah Tahmasp, the Safavid King, greeted Humayun warmly in Isfahan. After their stay in Isfahan, Humayun was provided with a 12,000 strong cavalry by the Safavids. With this force under his command, Humayun charged towards Kandahar where Akbar was staying with Askari and his wife. On learning about Humayun’s advance, Askari sent Akbar to Kabul. Akbar is described as a very intelligent child who possessed great strength.

After capturing Kandahar in September 1545, Humayun marched toward Kabul. Humayun captured Kabul in November and three-year-old Akbar was reunited with his parents. A few months later Akbar was again kidnapped by his uncle Kamran and Humayun had to make another raid to recover Akbar. He finally succeeded on April 28, 1547. At the age of eight years, Akbar was assigned Kabul’s governance with Muhammad Kasim Khan as his guardian. However, Humayun’s naivety again led him into trouble and Akbar fell in treacherous Kamran’s hands once again. Humayun again attacked his brother and, as he retrieved Akbar one more time, scored a decisive victory.

Humayun then marched toward Hindustan in November 1554 with his loyal general Bairam Khan and Akbar by his side. Humayun fought his way fiercely and Mughals recaptured Delhi from its Suri rulers on July 23, 1555, fourteen years after they had fled in ignominy. In January 1556, as he was leading the Mughal army in a battle in Haryana, young Akbar was told that his father had passed away in a freak accident. Emperor Humayun had fallen from the upper floor of his library and fatally injured his head. Not much different from how Babur’s father had been killed in a bizarre mishap when Babur was a young boy.

Like Humayun had to become the king at the age of 12 after Babur’s death, Akbar now became the king of Delhi empire at 13-year-old. But that is where the similarity ends. Akbar was of an entirely different mettle from his father. Akbar was coronated and declared Emperor on February 14, 1556. His kingdom, however, was unstable and barely controlled Delhi, Agra, and Punjab as powerful enemies abounded on all sides of his territory as well the intrigues within. Trusted Bairam Khan became Akbar’s regent. As the newly crowned Akbar was returning to Delhi, both Delhi and Agra were lost by his generals to Shah Adil’s forces. Meanwhile, on learning of Humayun’s death, Kabul’s governor also rebelled.

Akbar regrouped his army and came face to face with Delhi’s rulers in Panipat on November 5, 1556. He must have thought how, thirty years ago, his grandfather had scored a fabulous military victory on this very battleground. Like his grandfather, Akbar was also outnumbered with odds stacked against him. The historic battlefield of Panipat witnessed young Akbar’s first victory as an emperor. Thousands of his opponent soldiers lay dead on the battlefield as vultures hovered over them. Akbar then sent for women of the family who were still in Kabul. Hamida Begum who had left Hindustan as a fugitive’s wife, returned as an emperor’s mother. She would never again be separated from her beloved son and would stand strong by him in all his ventures. With Delhi under his feet, Akbar went on to make the entire Hindustan his too.

Within a few years Akbar got rid of Bairam khan as his methods and philosophy of ruling were very different from those of Akbar. They were more vicious. Akbar was on his own and at eighteen he was already adept at government and warfare. Bairam Khan went into rebellion and was defeated and captured. Akbar still treated him well and granted his wish to go to Mecca and also took Bairam’s son Rahim under his tutelage. Rahim Khan went on to become Khan-e Khanan and one of Akbar’s famous nine advisors (navratans).

Akbar’s volatile childhood had taught him to be mature from a young age. He had directly experienced people of various mindsets and clearly understood that the throne cannot be fettered by relations. His father’s life had served him an ample example that the king cannot be complacent or too trusting. Akbar was enormously intelligent, astute, ambitious, realistic, and thoughtful in his dealings with people and situations alike. While Akbar was merciful by nature, he knew what it takes to be a king. By the age of nineteen all the people who tried to exercise control over a young Akbar, conspired against him, or misused their close bonds with him were eliminated. The emperor would from now be the master of all his decisions, ready for his journey from Akbar to Akbar the Great, the greatest of all rulers of India since Ashoka.

Akbar was as successful in peace as he was in war. He possessed a very strong physique and was highly skilled in weapons, fighting, hunting, horse-riding, training cheetahs, and controlling enraged elephants. He strove to treat his subjects like his children and always endeavored to be as indiscriminate and fair toward them as possible. In that he was distinctively redolent of Samrat Ashoka. Akbar treated talented men like his brothers, no matter what their origin was. He described his relationship with his officials as being close and based on respect.

Akbar had a deep passion to understand his people – their lives, struggles, and joys. He would often disguise himself to roam in the city to learn more about the culture, sometimes becoming a part of thronging Indian crowds gathered for festivities. Before Akbar there was no Mughal Empire but only attempts to create one. Born to a fugitive, he left an empire that extended from Kabul to the Bay of Bengal and from Kashmir to the Vindhyas. He carved out a massive and prosperous Hindustani kingdom steeped in local culture and festivals. He took personal interest in promoting local arts, music, literature, and philosophy. He could recite local tales with appropriate gestures and delivery, could walk sixty kilometers from Mathura to Agra within a day for exercise, and sometimes even mingle with workers and artisans. He had an amazing eye for artistic, literary, intellectual, and governance talent and would pick them from anywhere.

Akbar was also a strict disciplinarian who behaved firmly with his officers whose punishments for wrongdoing were more severe than those for commoners. For example, when Akbar’s own chief trade commissioner was found guilty of sexual misconduct with a Brahmin girl despite himself being already married, Akbar ignored all pleas, treaties, and ransoms that were offered and made sure that regular punishment -death for rape and adultery- was meted out to the guilty commissioner. There are also many recorded cases of royal officers being whipped with leather thongs for misconduct.

Antonio Monserrate (1536-1600), a renowned Portuguese priest, who led the first Jesuit mission to Akbar’s court had this to say, “He was a prince beloved of all, firm with the great, kind to those of low state and just to all men, high or low, neighbor or stranger, Christian, Muslim or Hindu.” However, not everyone was supportive of Akbar’s broadmindedness and tolerance. Many orthodox members of nobility and ulema loathed his open outlook on religion and his inclusion of scholars of various faiths in the court. But Akbar was too mighty a monarch to care about their criticism. Born to a Shia mother and a Sunni father in the palace of a Hindu Rajput, Akbar felt absolutely at home in a diverse India.

Akbar’s innovative talents were not just limited to philosophical pursuits. He was also an innovative and a brilliant general. In a long and distinguished military career there are a number of instances manifesting Akbar’s prowess as a military commander. He constantly upgraded his troops in skills, tactics, and weaponry and maintained fearful discipline among his officers. He fought battles in various parts of India, and it is interesting how he varied his tactics and use of arms for different terrains.

Akbar was a curious man who surrounded himself with intelligent and learned men of an amazing diversity – writers, musicians, theologians, singers, philosophers, poets, astrologers, artists, and soldiers. How much Akbar loved to explore the world is reflected in these words by Du Jarric, “At one time he would be deeply immersed in the state affairs, or giving audience to his subjects, and the next moment he would be seen shearing camels, hewing stones, cutting wood or hammering iron, and doing all this with as much diligence as though engaged in his own particular vocation.” As Edward Gibbons wrote of Genghis Khan, Akbar too “Died in the fullness of years of glory.”

Zahir ud-din Muhammad Babur (1483-1530)

Babur is an astonishing and impressive persona. Shining as a writer, a king, a warrior, a general, and a thinker – Babur seems to have lived several lives within his relatively short existence of 47 years. Babur was a scion of two formidable conquerors in human history – Timur from his father’s side and Genghis Khan from his mother’s. However, he preferred to identify himself as of Timurid ancestry because his worst enemies, the Uzbeks, were also descendants of Genghis Khan.

When his father died in an accident, Babur was catapulted into being the ruler of Ferghana before he was twelve years old. Babur soon lost his throne because he was too young to understand and navigate the shenanigans that accompanied his crown. What followed was several years of a tough life as an itinerant fugitive. Only three women of his family -his sister, his mother, and his maternal grandmother- stood by Babur in those years beset with insecurities, hardships, and betrayals. Babur never stopped being deeply grateful to these women’s unconditional support to him when all seemed lost. During this time Babur also fell gravely ill on a few occasions. It was long before Babur could call himself the master of a stable territory. Babur reminisces in his diary to have cried at one point. He was fifteen then. However, at no point do Babur’s memoirs recount him having lost hope. This man did not know to give up.

In 1498 Babur rode out with a few companions and reconquered his father’s land, Ferghana. In 1500 Babur tried to conquer Samarkand and won. However, soon Shaibani, the wily ruler of Samarkand Babur had defeated, gathered force, and besieged Babur in the fort. Once again none of Babur’s relatives and clan came to his succor. Babur pens, “No one had helped me when I was in strength and power and had endured no beating or loss, on what count would they help me now?”

At this point Babur’s brave sister Khanzada agreed to marry Shaibani to save her brother’s life. Babur would have none of it, but Khanzada insisted. Valiant Khanzada was right, for otherwise Babur faced a certain death. Khanzada believed in Babur and knew that, if the empire was to be raised, nobody’s life in that moment was more precious to be saved than Babur’s. This was an act of massive sacrifice that etched an indelible mark on Babur’s young heart, not even twenty by then.

A disparaged Babur had to leave Samarkand, leaving his beloved sister behind with the enemy. Wearily, Babur went to Khalila and then to Dizak, where Babur was welcomed by his trusted man Tahir. Babur’s memoirs describe these happenings in life in details and with eloquence. Babur’s mother and grandmother were by his side, but his heart would long for his sister for years to follow. A still teenaged Babur writes, “Is there one brutal act of fate’s wheel unseen of me? Is there a twinge, an anguish my suffering heart has missed?”

In 1506 Babur took on a hazardous journey through snowy mountains to Kabul. It was a slow and perilous voyage. Babur persevered through it all, never leaving his men out alone in a storm or a blizzard to take refuge in a cave or a tent. He chronicles, “My troops outside in suffering and discomfort and I, inside sleeping comfortably! This would be anything but a man’s act, Whatever adversity, or misery there is, I will face; what strong men stand, I will stand.” That was Babur, a man of incredible valor and character, the stuff heroes are made of. Babur’s failures, agonies, and hardships only made him tougher to surmount obstacles.

Meanwhile, Safavid ruler Shah Ismail faced Shaibani in a battle and defeated and killed him. On learning that there was a Mughal princess among Shaibani’s people, he returned her to Babur with respect and honor. Thus, Khanzada was reunited with her brother after having stayed with the enemy for a decade. In 1524 Babur set his sights on North India and attacked Punjab. However, he did not achieve the desired success and withdrew to Kabul.

A year later, Babur was back in India and marched to Delhi. His 20,000 strong army encountered the massive force -over 100,000 soldiers and 1,000 elephants- of Delhi’s king Ibrahim Lodhi. Until then Babur’s conquests had taken place in the hilly landscapes of Central Asia where the enemy’s numerical superiority would be less of a disadvantage to Babur. Panipat, on the other hand, was a flat land that gave a much larger army a substantial advantage. “I put my foot in the stirrup of resolution, set my hand on the rein of trust in God, and moved forward against Ibrahim Lodhi,” writes Babur.

History has recorded in detail how Babur’s fearless military genius triumphed over Ibrahim Lodhi’s massive force. The battle culminated in merely five hours, ending the reign and life of the last Sultan of Delhi. Babur wrote, “By God’s mercy and kindness this difficult affair was made easy for us! In one-half of a day, that armed mass was laid upon the earth.” Babur was not exaggerating as almost a third of Delhi’s army was mowed down. The Khutba was read in Babur’s name, who treated Lodhi’s family with respect and generosity, even forgiving his mother when she tried to poison Babur and almost killed him. Babur’s memoirs recorded at length his first impressions of India. Hindustan was his territory now. Babur would never see his beloved Ferghana again in whose valleys and plains he galloped his horse as a young boy and would never realize his dream of conquering Timur’s Samarkand. Fate had willed him in a completely different direction.

Babur’s next adversary was Rana Sanga, the ruler of Mewar. He was much more challenging a foe than Ibrahim Lodhi with a military career of over a hundred battles that had left scars on every part of his body and an army of Afghans and Rajputs who were formidable fighters. This battle was crucial for Babur to establish his authority in North India. Babur’s army was once again vastly outnumbered along with the enemy once again having the advantage of elephants. Babur and Rana Sanga fought on 16th March 1527 at Khanwa near Agra. The battle ended in a mighty victory for Babur. The following year Babur scored another decisive victory at the Battle of Chanderi against Medini Rai. Then Babur dealt with the Afghan threat in the east with a victory at the Battle of Ghaghra in 1529. Babur had come a long way from the orphaned child heir who was betrayed and lost his territory in Ferghana. He now ruled a vast territory as the indomitable founder of a famous empire in a distant land. He died in 1530 at the age of 47 and just four years after his conquest of India.