While thinking of how most Pakistanis grudge Malala’s Nobel Prize for Peace, which she by no means got undeservedly, my mind wandered to a man who turned down a Nobel Prize.

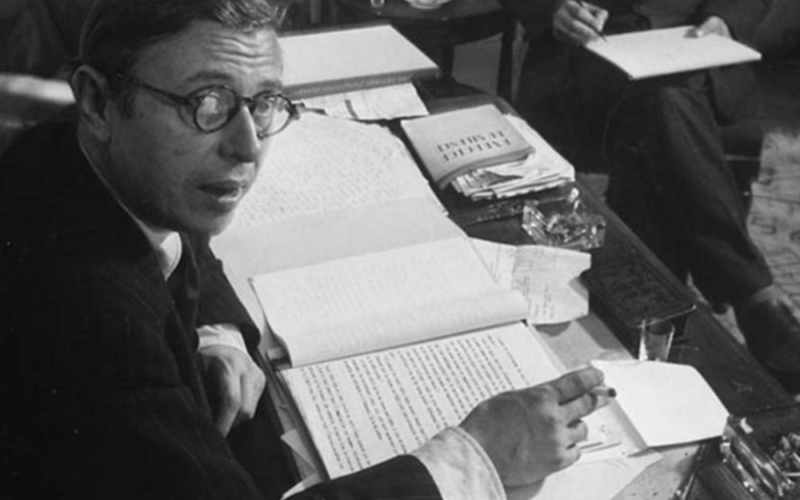

On October 22 1964 Jean-Paul Sartre declined the Nobel Prize for literature, saying “I have always declined official honours. A writer should not allow himself to be turned into an institution. This attitude is based on my conception of the writer’s enterprise. A writer who adopts political, social or literary positions must act only within the means that are his own – that is, the written word.” Sartre learned from Figaro Littéraire that he was in the reckoning for the award, he then wrote to the Swedish Academy saying he did not want the prize. The prize was awarded to him nevertheless. “I was not aware at the time that the Nobel Prize is awarded without consulting the opinion of the recipient,” he said. “But I now understand that when the Swedish Academy has made a decision, it cannot subsequently revoke it.” His honourable stance cost him 250,000 kronor (about £21,000), prize money that, he regretfully reflected in his refusal declaration, he could have donated to a worthy cause like the “apartheid committee in London.”

Sartre’s views of literature

Sartre always tormented himself about the purpose of literature, advocating that literature must have a dyed-in-the-wool social purpose. However, Sartre’s latter writings betray despondency over that purpose. In his memoir Words, an eternally dazzling piece of work, he wrote: “For a long time I looked on my pen as a sword; now I know how powerless we are.” He thought that politically committed literature makes nothing happen and fretted that Nobel was reserved for “the writers of the west or the rebels of the east.” He said that he would have deserved the Nobel much better if it had been awarded to him for his passionate antagonism to France’s war of occupation in Algeria because the award would have then helped his struggle rather than turning Sartre into a depoliticized brand or institution. I have always had a great respect for his qualms.

Why he was given the prize

The Swedish Academy had selected Sartre for having “exerted a far-reaching influence on our age”, though that hardly seemed the case at that moment. Although widely acknowledged as a colossal thinker of his times, his reputation as a philosopher was remarkably on the decline with his trademark existentialism already put into shade and derided by the structuralists and post-structuralists by the time the award was offered to him. While he was still glorified by student radicals in France, Anglo-Saxon was predominantly sceptical about Sartre’s merit as a philosopher. He was relentlessly described as a typical pantomime figure, allegedly repulsive, unintelligible, quixotic, and caught up in philosophical jargon. He deserved better.

Swedish Academy was right

The Swedish Academy was right. Much of Sartre’s life’s intellectual output and his work are still relevant. Even today, when we read his assertion we can, through head and action, transform our destiny, we feel the eternal burden of responsibility of choice to become moral beings. His lifetime dedication to opposing fascism and imperialism still reverberate in a world of rampant religious fascism and uni-polar chemistry of international politics. His play Huis Clos reminds us of the irony of our relations with other people as we need them to validate our self-images, whereas they –much to our irritation- require us to confirm theirs. Sartre makes us think about the paradox of being a human that makes us yearn for a complete control over our destiny and identity, and at the same time, forces us to acknowledge the futility of that desire. Sartre giftedly identified the existential dilemma of humanity, the absurdities of life, our moral choices, and our political responsibilities that still resonate with us as loud as ever.

Sartre as an activist

Sartre is one of those writers for whom a resolute philosophical position is the heart of their artistic life. Declaring, “Commitment is an act, not a word,” Sartre often participated in street riots, in the promotion of left-wing literature, and in other activities to advocate the revolution. He was a vocal backer of the student movement in France of May 1968, soaring to unusual height in his indictment of the Communist Party as having betrayed the May revolution. He remained politically involved by editing and supervising the publication of various Leftist publications.

Sartre’s writings

While the publication of his early, largely psychological studies, L’Imagination (1936), Esquisse d’une théorie des émotions (Outline of a Theory of the Emotions), 1939, and L’Imaginaire: Psychologie Phénoménologique de l’Imagination (The Psychology of Imagination), 1940, did not gain much attention, Nausea and the collection of stories Le Mur (Intimacy, 1938), quickly brought him recognition. Both in the novel and in these stories one can find the currents of Sartre’s interest in existentialism and its themes. In his first novel La Nausée (Nausea, 1938), the central character, Antoine Roquetin, discovers an obscene unreasonableness of the world around him, inducing in his own loneliness experiences of a totalizing, psychological nausea. It is a story of life without purpose, in which Sartre portrays an awful rationality and fixity of the ordinary nature of bourgeois culture, which he compares to an imposing strength of stones on the seashore.

Although extracted from many sources, the existentialism Sartre devised and popularized is very much original. Its recognition and that of its author reached a pinnacle in the forties, and Sartre’s writings as well as his novels and plays make up an inspirational source of modern literature. His philosophical outlook takes atheism for granted and the loss of God is not mourned. Man is designed for a freedom from all power, which he may try to escape, twist, or reject but which he cannot avoid dealing with if he has to become a moral being. Once he acknowledges his freedom, man has to establish the meaning of his life as this meaning is not established before his existence. Thus he has to commit himself, his freedom, to a role in the world. Sartre sets forth in “Qu’est-ce que la littérature?” (What Is Literature?), 1948, that literature is not an activity for itself, nor first and foremost expressive of characters and situations, but deals with human freedom. In his view Literature has to be committed and artistic creation a moral activity. These existentialist themes of alienation and commitment and of salvation through art dominate his life’s work. The existentialist humanism which Sartre constructs in his popular essay “L’Existentialisme est un humanisme” (Existentialism is a Humanism), 1946, is propagated in the series of novels, “Les Chemins de la Liberté” (The Roads to Freedom), 1945-49.

His fundamental philosophical work, “L’Etre et le Néant” (Being and Nothingness), 1943, is a gigantic articulation of his concept of being, from which much of modern existentialism develops. This is his most powerful work, in which he makes the distinction between things that exist in themselves (en-soi) and human beings who exist for themselves (pour-soi). Human beings live with an understanding of the limits of knowledge and mortality, therefore in a state of existential dread. The loss of God is not mourned, for humankind is condemned to freedom, and from all authority, that must be faced if one is to become a moral being. The acceptance of the dreadful freedom then requires man to make meaning for himself (by the detachment of oneself from things so as to lend them meaning) and commit to a role within this world — this is useless without the solidarity of others. Sartre’s Cartesian view of the world extended to the creation of the world by the self through detachment, by rebelling against authority and accepting personal responsibility for one’s own actions, without aid by society, traditional ideas of morality or religious faith. The realm or the human world, as differentiated from the non-human, is characterized by nothingness, by the human capacity for negation and rebellion. The recognition of one’s absolute freedom of choice is the fundamental condition for authentic human existence.

Sartre’s Existentialism

Sartre considers that Existentialism is of two main types: Religious Existentialism and Atheistic Existentialism. He says that his philosophy comprises Atheistic Existentialism. The cardinal principle of Existential Philosophy, Religious or Atheistic, is that Existence precedes the Essence. Which means that, regarded logically, the starting point for any rationalization of man’s experience is in the realm of subjectivity. Existentialism proposes that there is nothing prior to the act of existence, of which man is aware directly and immediately. Immediacy of existence gives us the act of existence and there is nothing that precedes the existence. Thus the principle of “Cogito-Ergo-Sum” is the starting point of Existential Philosophy. In practical terms, this viewpoint eliminates anything that may be regarded as a metaphysical ground of existence. Existential Philosophy asserts that because existence is prior to essence, in all our choices and all our decisions we act freely, in complete freedom from all the factors that are independent to our will. In my view, just as the proponents of the Philosophy of Determinism commit the mistake of denying the creative nature of human consciousness and make the will appear as servile and obedient slave of the forces that drive it, Sartre and Existentialists commit the opposite mistake of totally denying the influence of environment, heredity, and other factors that are an essential part of man’s genetic and psychological constitution.